Christianity has always been a global religion,” Dr. Vince Bantu says at the start of the first talk in his lecture series “Early African And Asian Christianity” (see below for information on Seminary Now). It’s a startling claim for those of us who grew up learning about the history of the church through a Western lens, one that suggests Christianity went from “the West to the rest” as part of our colonial evangelistic efforts. Yet we know that at Pentecost people from all over the world were present, and they took that gospel message in every direction, including to what we now call Asia, Africa, and, yes, Europe. In each of these places the gospel took root and flourished, worship and other Christian practices developed, and wise and knowledgeable theologians grappled with the meaning of Scripture.

I am excited that Dr. Bantu has agreed to write a series of articles for Reformed Worship’s “Learning from History” column because it is important for worship leaders and pastors to glean from the wisdom of the past and see how we stand both in continuity and discontinuity with the church in all times, including the church in Africa and Asia. A few articles won’t do the topic justice, but maybe they will be enough to get us interested in learning more.

There is another reason this series is significant this year as Reformed Worship focuses on the connection between worship and missions: No matter where one’s church is located, there are people in the community with non-Western roots. And, according to Bantu, “The perception that Christianity is a Western religion is the single greatest barrier to people coming to faith in Jesus Christ. . . . This work of history is not only historical, but it’s also evangelistic and missional. We have to help people understand that Christianity is not becoming a global religion. It didn’t just go from the West to the rest. But Christianity . . . has been global from the very beginning” (Bantu, Seminary Now, see below). If as worship leaders and pastors we want to change people’s perception of Christianity, we must learn from the practices of the Christian church in other parts of the world—and from their church leaders and theologians. If we want to sing “God’s got the whole world in his hands,” we need to understand what that looked like in the past and what it looks like today.

—Joyce Borger, senior editor

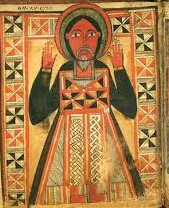

In many parts of the world, the celebration of the nativity of Jesus—Christmas—is the most celebrated holiday of the year. For many Christians in the Horn of Africa, however, there is another annual commemoration that draws even greater attention: the Feast of the Epiphany. For different Christians around the world, the Feast of the Epiphany may commemorate the visit of the Magi, Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan River, or the wedding at Cana (the occasion for Jesus’ first recorded miracle). For Christians of Ethiopia and Eritrea, Epiphany—known as Timket—is always the week in January (or Tir) in which the baptism of Christ is celebrated. In the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia and Eritrea, Geʿez, the word timket means “baptism.” During the Feast of Timket, Ethiopian and Eritrean Christians celebrate the Lord’s Supper in the middle of the night, engage in processions of the Ark of the Covenant (Tabot), and baptize people in pools. Some of the most famous pools in Ethiopia are the pool of the Queen of Sheba in Axum and the pool complex of Emperor Fasil. Clothing, banners, and other decorations proudly use the red, green, and yellow of the Ethiopian flag.

Timket is a time in which Ethiopian and Eritrean identity is celebrated and centered on the person and work of Jesus Christ. The baptism of Jesus is seen as one of the best illustrations of the full humanity and full divinity of Christ.

The earliest documented prose author in the history of the Horn of Africa—and sub-Saharan Africa in general—wrote a comprehensive systematic theology in the early 1400s. His name was Giyorgis of Sagla, and he is still regarded as one of the most important authors in Ethiopian and Eritrean history. Each chapter of Giyorgis’s Book of Mystery addresses a different theological topic and is meant to be recited publicly during the liturgy on particular feast days. The sixth chapter was written specifically for the occasion of Timket. It vividly summons the church to enter into the baptism of Jesus and experience it with him. Giyorgis here personifies the global church as a woman experiencing baptism:

[She] proceeded toward the Jordan River, seeking to be baptized in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. She descended into the waters of the Jordan at once to be baptized in the name of God the Father (ʾƎgziʾabḥer lit: “Lord of the lands”), who bore witness to the Son in the baptismal. She was also baptized in the name of God the Son(ʾƎgziʾabḥer), who was baptized by the hand of John, son of Zechariah; and then, thirdly, she was baptized in the name of God the Holy Spirit (ʾƎgziʾabḥer), who came down from the heavens and rested upon the head of the Lord (ʾƎgziʾ) Jesus in the bodily form of a dove. Then, coming out of the waters of the Jordan, she received the seal of anointing by the tongue, just as was heard in the time of Christ. For the anointing by the tongue is the power of faith (haymanot).

—Giyorgis of Sagla, Mäṣḥäfä Mǝsṭir, ed. Yaqob Beyene, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 515, Scriptores Aethiopici 89, 1999, p. 150. Translated by Vince Bantu, presented here in English for the first time.

Giyorgis emphasized the role of the Trinity (Śellase) in the baptism of Jesus because the occasion for this chapter was the refutation of subordinationist Christology. People in the northern Ethiopian Highlands in Giyorgis’s day were teaching that Jesus was inferior to God the Father. For this reason Giyorgis begins this chapter with a poem that worships the three persons of the Trinity:

In the name of God (ʾƎgziʾabḥer),

who is triune (Śelso) according to the ordinances of the Nazarenes,

whom we declare holy along with the voice of the seraphim,

who has placed His throne in the palace of the highest heaven,

where human hands cannot touch it and mortal minds cannot investigate,

who causes the vapor of clouds at the summit of mountains to smoke and removes it without a sound and causes it to mingle in the atmosphere,

who clothes the expansive face of the sky with a garment of clouds,

He is worthy of glory and praise forever and ever,

Amen.

—Giyorgis, Mäṣḥäfä Mǝsṭir, p. 144.

Each chapter of Giyorgis’s Book of Mystery begins with similar poetry that summons the congregation to worship and prepares their minds for theological instruction in a liturgical context. Giyorgis clearly felt that on Timket, the feast day of the baptism of our Lord, it was most important to reflect on the full humanity and full divinity of Jesus Christ. And now, six hundred years later, we can join the congregation of Giyorgis in celebrating the divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ as we reflect on the glory displayed at his baptism.